Quantum Computing Is Moving From Physics to Engineering

Introduction

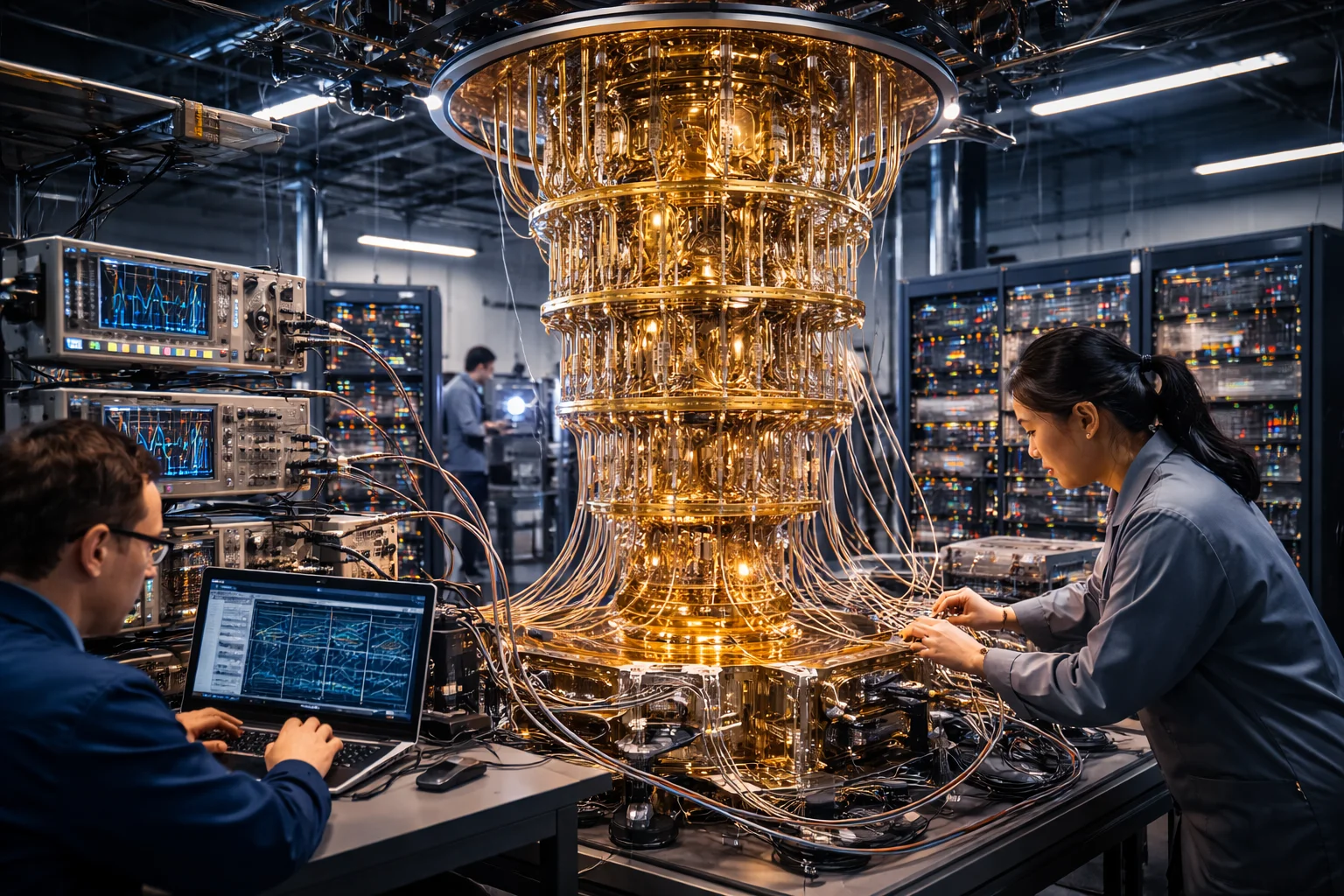

The quantum computing industry is undergoing a fundamental shift. What began as a pursuit of theoretical physics is increasingly becoming a discipline of systems engineering. Major technology companies and startups are moving beyond proof-of-concept demonstrations to tackle the complex engineering challenges required to build practical quantum systems. This transition involves scaling quantum hardware, developing robust control systems, and addressing the mundane but critical infrastructure requirements that determine whether quantum computers can operate reliably outside research laboratories.

This evolution represents a maturation of the field, but it also reveals the substantial technical and economic hurdles that remain. Understanding where quantum computing stands today requires examining not just the physics breakthroughs, but the engineering problems that companies are solving to make quantum systems viable for enterprise applications.

Background

Quantum computing has historically been dominated by physics research focused on maintaining quantum coherence and implementing quantum gates. Early milestones centered on achieving quantum supremacy or quantum advantage—demonstrating that quantum computers could solve specific problems faster than classical computers, even if those problems had limited practical application.

The field's trajectory changed as companies like IBM, Google, and startups such as IonQ and Rigetti began building quantum computers intended for commercial use. These efforts revealed that the path from laboratory demonstration to practical deployment requires solving engineering challenges that extend far beyond the quantum processor itself.

Modern quantum computers require sophisticated control systems, cryogenic infrastructure, error correction protocols, and software stacks that can interface with classical computing environments. The quantum processor represents only a fraction of the overall system complexity. Companies have discovered that maintaining quantum states requires engineering precision comparable to semiconductor manufacturing, but with additional constraints imposed by quantum physics.

The transition has accelerated as quantum computing attracts enterprise attention and investment. Organizations evaluating quantum computing for optimization, simulation, or cryptographic applications need systems that integrate with existing IT infrastructure, provide consistent performance, and operate reliably over extended periods. These requirements push quantum computing from experimental physics toward systems engineering.

Key Findings

Hardware Scaling Faces Physical and Engineering Constraints

Quantum computing progress 2026 projections suggest that hardware scaling will be limited by engineering constraints rather than fundamental physics. Current quantum processors operate with dozens to hundreds of qubits, but scaling to thousands of qubits requires addressing interconnect complexity, control signal routing, and thermal management at cryogenic temperatures.

IBM's quantum roadmap illustrates these challenges. The company's processors have grown from 5 qubits in 2016 to over 1000 qubits in their Condor processor. However, each scaling step has required engineering innovations in packaging, wiring, and control electronics. The physical constraints of routing thousands of control lines to individual qubits while maintaining isolation from electromagnetic interference become increasingly difficult as systems grow.

Google's approach with their superconducting quantum processors demonstrates similar engineering tradeoffs. Their Sycamore processor achieved quantum supremacy with 53 qubits, but scaling beyond this required redesigning the control architecture to minimize crosstalk between qubits and improve gate fidelity. The engineering challenge involves balancing qubit density with the physical space required for control lines and isolation.

Ion trap systems from companies like IonQ face different scaling constraints. While individual ions can achieve high gate fidelities, scaling requires precise control of electromagnetic fields across larger arrays. The engineering challenge involves maintaining field uniformity and minimizing heating effects that can destroy quantum coherence.

Control Systems Engineering Becomes Critical Bottleneck

Quantum control systems engineering has emerged as a specialized discipline requiring expertise in high-frequency electronics, real-time systems, and quantum physics. These systems must generate precise control signals with nanosecond timing while operating in the presence of electromagnetic noise and temperature variations.

Classical control electronics for quantum computers operate at room temperature but must control quantum states at millikelvin temperatures with extraordinary precision. The engineering challenge involves designing control systems that can maintain phase coherence across thousands of control channels while adapting to drift in the quantum processor.

Companies like Zurich Instruments and Quantum Machines have developed specialized control hardware for quantum computing applications. Their systems integrate classical signal processing with quantum-specific requirements such as real-time quantum feedback and error correction protocols. The engineering complexity rivals that of high-end test and measurement equipment but with custom requirements for quantum applications.

The software stack for quantum control systems represents another engineering challenge. Companies must develop real-time operating systems that can coordinate classical and quantum operations with precise timing constraints. This software must interface with quantum programming languages while managing the low-level control of quantum hardware.

Infrastructure Requirements Mirror Data Center Engineering

Quantum systems engineering increasingly resembles data center infrastructure planning. Quantum computers require specialized cooling systems, power conditioning, electromagnetic shielding, and vibration isolation that must operate reliably for years rather than hours.

Cryogenic systems for quantum computers consume significant power and require regular maintenance. A typical dilution refrigerator used to cool superconducting quantum processors consumes 15-25 kilowatts of electrical power to maintain temperatures below 20 millikelvin. The engineering challenge involves designing cooling systems that can maintain stable temperatures while accommodating thermal loads from control electronics.

Electromagnetic shielding represents another infrastructure engineering challenge. Quantum computers require isolation from radio frequency interference that would destroy quantum coherence. This requires designing facilities with specialized shielding and careful attention to grounding and electromagnetic compatibility. The engineering requirements resemble those of sensitive measurement laboratories but with additional constraints imposed by the need for reliable operation.

Error Correction Transitions from Theory to Implementation

Quantum error correction is moving from theoretical proposals to practical implementation, revealing the engineering complexity required to build fault-tolerant quantum computers. Current quantum processors exhibit error rates that require correction to achieve practical applications, but implementing error correction requires scaling quantum systems by orders of magnitude.

IBM's quantum error correction roadmap illustrates the engineering challenge. Their approach requires approximately 1000 physical qubits to create a single logical qubit with reduced error rates. This scaling requirement means that practical fault-tolerant quantum computers will require tens of thousands of physical qubits, each with associated control systems and infrastructure.

Surface code implementations being developed by Google and other companies require two-dimensional arrays of qubits with specific connectivity patterns. The engineering challenge involves designing quantum processors with the required qubit layout while maintaining low error rates across the entire system. This requires innovations in qubit fabrication, control systems, and classical processing hardware.

Manufacturing and Quality Control Emerge as Differentiators

Quantum hardware manufacturing is developing quality control processes similar to semiconductor fabrication, but with additional complexity imposed by quantum physics. Companies must control fabrication tolerances that affect quantum coherence while scaling to higher production volumes.

Superconducting quantum processors require fabrication processes that can control material properties at the nanometer scale while maintaining consistency across large wafers. IBM's quantum processor fabrication uses semiconductor manufacturing techniques but with additional process controls required to achieve the electrical and magnetic properties needed for quantum operation.

Ion trap quantum computers require precision machining and assembly of electromagnetic trap structures with tolerances that affect ion positioning and control field uniformity. The manufacturing engineering challenge involves scaling precision fabrication techniques while maintaining the quality required for quantum operation.

Quality control for quantum systems requires testing procedures that can verify quantum performance without destroying the quantum states being measured. This has led to the development of specialized test equipment and procedures that can characterize quantum systems and identify manufacturing defects that would affect quantum performance.

Implications

The engineering focus of quantum computing has significant implications for enterprise adoption and industry development. Companies evaluating quantum computing must now consider not just algorithmic advantages, but system reliability, integration complexity, and operational requirements that affect total cost of ownership.

Enterprise quantum computing deployments will require specialized facilities and support staff comparable to high-performance computing installations. This represents a significant infrastructure investment that affects the business case for quantum computing adoption. Organizations must evaluate whether quantum advantages justify the infrastructure and operational complexity.

The shift toward engineering also affects the competitive landscape in quantum computing. Companies with strong systems engineering capabilities may have advantages over those focused primarily on quantum physics research. This suggests that established technology companies with experience in complex systems integration may compete effectively with quantum computing startups.

Supply chain considerations become increasingly important as quantum computing scales. The specialized components required for quantum systems—from cryogenic systems to high-frequency electronics—represent potential bottlenecks for industry growth. Companies must develop supplier relationships and manufacturing capabilities that can support scaling quantum systems.

The engineering requirements for quantum computing also affect the skills and expertise needed in the industry. Companies need engineers with experience in cryogenic systems, high-frequency electronics, and precision manufacturing in addition to quantum physics expertise. This multidisciplinary requirement affects hiring and training strategies for quantum computing companies.

Considerations

Several factors affect the interpretation of quantum computing's engineering transition. The timeline for practical quantum applications remains uncertain and depends on solving engineering challenges that may prove more difficult than anticipated. Companies making quantum computing investments should consider the risk that engineering constraints may limit near-term applications.

The quantum computing engineering challenges are interdependent, meaning that progress in one area may be limited by constraints in others. For example, scaling quantum processors may be limited by control system complexity rather than qubit fabrication capabilities. This interdependence affects development priorities and resource allocation decisions.

Cost considerations for quantum computing systems remain poorly understood because the technology has not achieved commercial scale. The engineering complexity suggests that quantum computers will remain expensive for the foreseeable future, potentially limiting applications to high-value problems where quantum advantages justify the cost.

The quantum computing industry is still developing standards for system interfaces, performance metrics, and quality control procedures. This lack of standardization creates risks for early adopters and may affect the ability to integrate quantum systems with existing enterprise infrastructure.

Quantum computing engineering also depends on advances in classical computing and electronics that are outside the quantum computing industry's direct control. Progress in areas such as high-frequency electronics and precision manufacturing affects the capability and cost of quantum systems.

Key Takeaways

• Quantum computing is transitioning from physics research to systems engineering, with hardware scaling limited by engineering constraints rather than fundamental physics principles

• Control systems engineering has become a critical bottleneck, requiring specialized expertise in high-frequency electronics, real-time systems, and quantum-specific control protocols

• Infrastructure requirements for quantum computers mirror data center engineering complexity, including specialized cooling, power, shielding, and facility requirements

• Manufacturing and quality control processes are emerging as competitive differentiators, requiring precision fabrication techniques and specialized testing procedures

• Enterprise adoption must consider system reliability, integration complexity, and operational requirements beyond algorithmic advantages

• The engineering transition affects competitive dynamics, potentially favoring companies with strong systems integration capabilities over pure research organizations

• Quantum computing's engineering challenges are interdependent, meaning progress requires coordinated advances across hardware, software, and infrastructure components