Why Error Correction — Not Qubit Count — Is the Real Bottleneck in Quantum Computing

Introduction

The quantum computing industry has developed an unhealthy obsession with qubit count. IBM announces 1,000-qubit processors, Google demonstrates quantum supremacy with 70 qubits, and IonQ markets systems with 32 "algorithmic qubits." These headlines create the impression that more qubits automatically translate to more computing power, but this narrative obscures the fundamental challenge that actually determines when quantum computers will deliver practical value: quantum computing error correction.

While companies continue the race for higher qubit counts, the real engineering bottleneck lies in managing quantum error rates and achieving fault-tolerant operations. Current quantum systems experience error rates that make them unsuitable for most practical applications, regardless of how many qubits they contain. Understanding why error correction represents the critical path forward reveals both the current limitations of quantum hardware and the timeline for meaningful quantum advantage in enterprise applications.

Background

Quantum computing fundamentally differs from classical computing in how information is processed and stored. Classical bits maintain stable states of 0 or 1, while quantum bits (qubits) exist in superposition states that enable parallel computation. However, this quantum advantage comes with a critical vulnerability: quantum states are extremely fragile.

Quantum error rates in contemporary systems range from 0.1% to 1% per operation, compared to error rates of approximately 10^-15 in modern silicon processors. A typical quantum algorithm might require thousands or millions of operations, causing errors to accumulate rapidly. Without correction, these error rates make quantum computations unreliable for any application requiring consistent, accurate results.

The physics behind quantum computing limitations extends beyond simple manufacturing tolerances. Qubits interact with their environment through electromagnetic fields, temperature fluctuations, and cosmic radiation. These interactions cause decoherence, where quantum information degrades over time. Current quantum systems maintain coherence for microseconds to milliseconds, while useful quantum algorithms often require computation times measured in seconds or longer.

Three primary error sources affect quantum systems: gate errors during quantum operations, measurement errors when reading qubit states, and coherence errors from environmental interference. Each error type requires different mitigation strategies, and all must be addressed simultaneously to achieve fault-tolerant quantum computing.

Key Findings

Current quantum hardware demonstrates a fundamental mismatch between qubit count and computational capability. IBM's 1,121-qubit Condor processor, for example, cannot reliably execute quantum algorithms that require more than 50-100 coherent operations due to accumulated errors. The system has impressive physical qubit count but limited logical computing power.

Quantum computing error correction requires significant overhead in terms of physical qubits. Leading error correction schemes, such as surface codes, typically require 1,000 to 10,000 physical qubits to create a single logical qubit that can perform reliable computations. This ratio means that IBM's 1,121-qubit processor could potentially support only one error-corrected logical qubit under ideal conditions.

The mathematics of quantum error correction reveal why qubit count alone provides limited insight into system capability. Error correction codes must detect and fix errors faster than new errors appear. Current quantum systems have error rates around 10^-3 per operation, while fault-tolerant quantum computing requires logical error rates below 10^-12 for practical applications. Achieving this improvement requires not just more physical qubits, but exponentially better error correction efficiency.

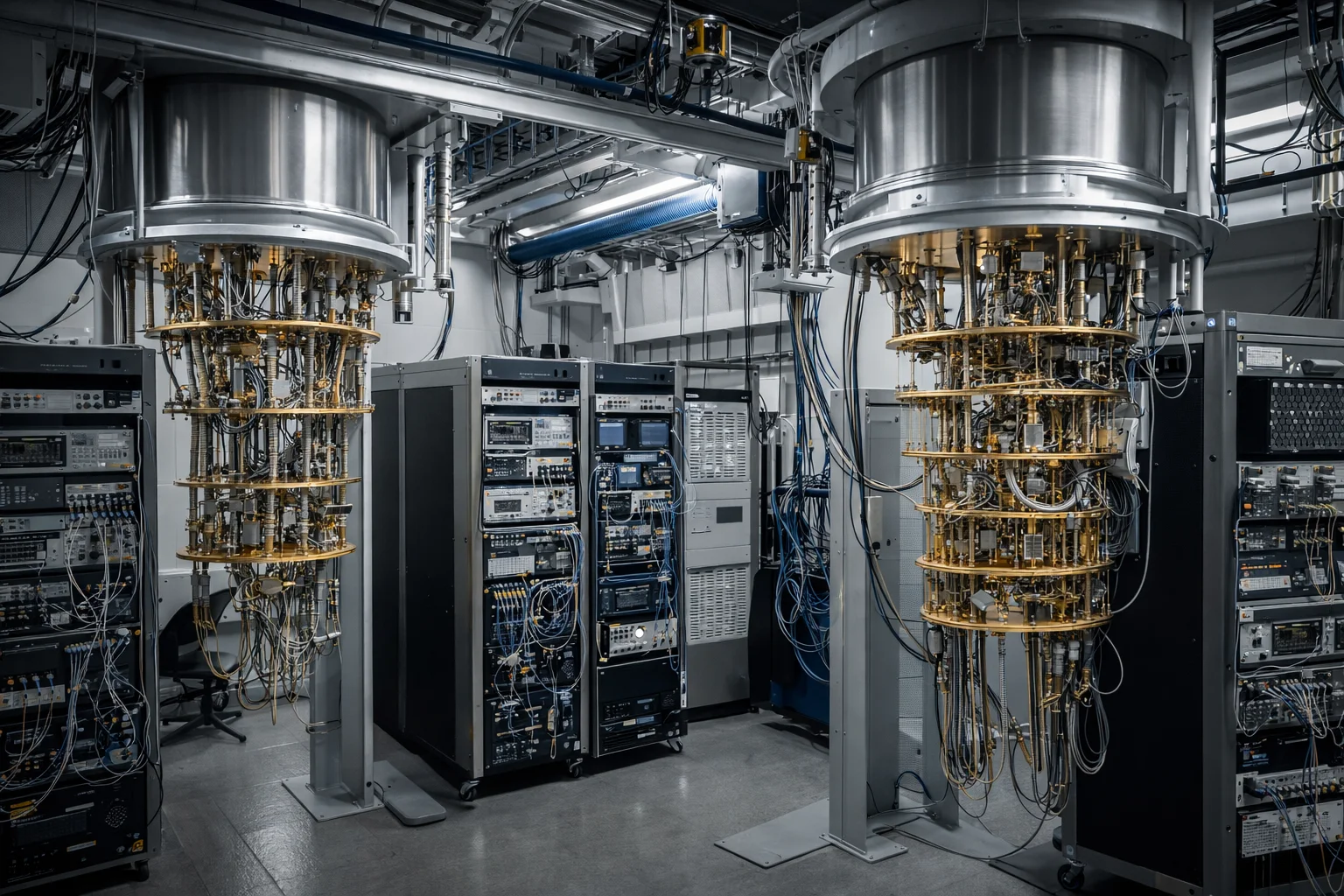

Industry efforts to address quantum computing scalability issues have produced several competing approaches. Topological qubits, developed by Microsoft in partnership with academic institutions, promise inherently lower error rates but remain in early research phases. Trapped ion systems from IonQ and others achieve higher gate fidelities but face challenges scaling to large qubit counts. Superconducting systems from IBM, Google, and Rigetti offer faster gate operations but struggle with shorter coherence times.

Real-world quantum computing limitations 2026 projections from major research institutions suggest that fault-tolerant systems will require millions of physical qubits to run meaningful algorithms. Current manufacturing capabilities cannot approach this scale while maintaining the precise control and isolation required for quantum operations. The engineering challenges include fabricating millions of nearly identical quantum devices, implementing real-time error correction at microsecond timescales, and maintaining system coherence across large arrays of qubits.

Corporate quantum strategies reflect awareness of these error correction challenges. Amazon's Braket service focuses on hybrid algorithms that minimize quantum circuit depth, reducing error accumulation. Microsoft's quantum development approach emphasizes software tools and error correction research rather than racing for maximum qubit count. These strategies acknowledge that practical quantum advantage requires managing errors, not just adding qubits.

The gap between quantum computing reality vs hype becomes apparent when examining specific algorithm requirements. Shor's algorithm for factoring large integers, often cited as a quantum computing application with clear economic value, requires millions of error-corrected operations to factor numbers relevant for current cryptographic systems. Running Shor's algorithm on today's quantum hardware would require error correction capabilities that exceed current technology by several orders of magnitude.

Implications

Enterprise quantum computing strategies must shift from qubit-focused metrics to error-rate and coherence-focused evaluation criteria. Organizations evaluating quantum computing investments should prioritize vendors demonstrating improvements in gate fidelity, coherence time, and error correction efficiency rather than raw qubit count. This reframing affects procurement decisions, partnership strategies, and internal research directions.

Quantum computing hardware challenges create a timeline mismatch between current marketing and practical deployment. While companies continue announcing increasingly large qubit systems, the fundamental error correction bottleneck suggests that practical quantum advantage for most applications remains years away. This reality impacts enterprise technology roadmaps and capital allocation decisions for organizations considering quantum computing integration.

The economics of quantum computing development favor approaches that address error correction directly. Research funding, venture capital investment, and corporate development resources currently flow toward companies promising higher qubit counts, but sustained quantum advantage requires breakthrough advances in error mitigation. Organizations with finite resources should prioritize error correction research over qubit scaling efforts.

Quantum computing talent acquisition and development programs must emphasize error correction expertise alongside quantum algorithm development. The engineering skills required to build fault-tolerant quantum systems differ significantly from those needed to design quantum algorithms. Organizations building quantum capabilities need specialists in quantum error correction codes, real-time control systems, and precision measurement techniques.

Quantum software development paradigms must evolve to work within error correction constraints. Current quantum programming models often ignore error rates and coherence limitations, creating algorithms that cannot run reliably on physical hardware. Practical quantum software requires error-aware design patterns that optimize for fault tolerance rather than theoretical computational complexity.

Considerations

Quantum error correction research faces several fundamental limitations that may constrain progress regardless of engineering advances. The quantum error correction threshold theorem requires error rates below specific thresholds that may prove difficult to achieve with certain qubit implementations. If physical error rates cannot reach these thresholds, no amount of additional qubits will enable fault-tolerant operation.

Different quantum computing approaches present distinct error correction tradeoffs. Photonic quantum systems promise lower error rates but face challenges with deterministic gate operations. Neutral atom systems offer flexible connectivity but struggle with gate speed consistency. These architectural differences mean that error correction strategies cannot be applied universally across quantum platforms.

The measurement problem in quantum error correction introduces additional complexity beyond simple error rate calculations. Measuring quantum states to detect errors inherently disturbs those states, creating measurement-induced errors that must be factored into correction schemes. This fundamental quantum mechanical limitation affects all error correction approaches and may require novel measurement techniques.

Resource requirements for quantum error correction extend beyond qubit count to include classical computing infrastructure. Real-time error correction requires classical processors capable of analyzing measurement data and computing corrections within quantum coherence times. These classical computing requirements represent significant additional cost and complexity for fault-tolerant quantum systems.

Economic factors may influence error correction development priorities in ways that do not align with technical optimality. Companies facing competitive pressure to demonstrate progress may continue emphasizing qubit count metrics even when error correction represents the critical bottleneck. This misalignment between market incentives and technical requirements could slow overall progress toward practical quantum computing.

Key Takeaways

• Error rates, not qubit count, determine quantum computing capability: Current quantum systems have error rates 12 orders of magnitude higher than required for fault-tolerant computing, making additional qubits ineffective without corresponding error correction improvements.

• Quantum error correction requires massive physical resource overhead: Leading correction schemes need 1,000-10,000 physical qubits per logical qubit, meaning current 1,000+ qubit systems can support at most one error-corrected logical qubit.

• Enterprise quantum evaluation should focus on error metrics: Organizations assessing quantum systems should prioritize gate fidelity, coherence time, and error correction capability over raw qubit specifications when making technology decisions.

• Practical quantum advantage timelines depend on error correction breakthroughs: Most commercially relevant quantum algorithms require error rates below 10^-12, representing improvement factors of billions compared to current hardware capabilities.

• Quantum computing scalability faces fundamental physics constraints: Error correction must outpace error generation, requiring advances in measurement techniques, real-time classical computing, and quantum control systems beyond simple manufacturing improvements.

• Different quantum platforms present distinct error correction challenges: Superconducting, trapped ion, photonic, and topological approaches each require specialized error mitigation strategies that cannot be universally applied across architectures.

• The quantum computing industry must realign development priorities: Sustained progress toward practical quantum computing requires shifting resources from qubit scaling efforts toward error correction research and fault-tolerant system engineering.